Norman Kirk was the first politician I was truly aware of as a kid. I remember as a tender wee seven-year-old, seeing the mountain of a man on the news, the first famous person beyond Basil Brush to register in my world.

I also vividly remember hearing the news that Norman Kirk died on August 31, 1974: I was mere days away from turning eight years old, and we were on a family holiday in the “Big Smoke” (aka Dunedin) when the news broke.

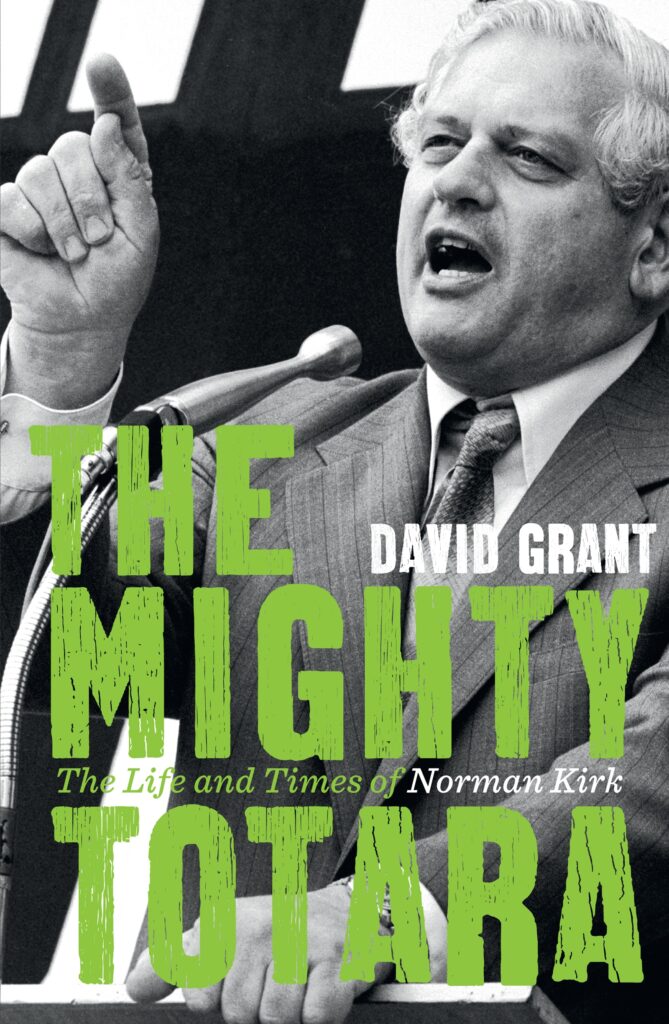

The title of this book – The Mighty Totara – comes from the words of a kaumatua, who called out “the mighty totara has fallen” as Kirk’s body lay in state near the steps of Parliament the day after his death. It’s a lament and a description that accurately sums up the feeling of the nation on losing the man, and also the level of respect for him across party lines and throughout the country. The entire nation mourned as his official funeral took place in Wellington on the day I turned eight.

He was our 29th prime minister and leader of the Labour Party, and given the impact he had on New Zealand and New Zealanders, it’s hard to believe he clocked up fewer than two years in the office before his death. He was just 51 when he died and more than 30,000 people filed past his coffin to show their respect over two days, and again in Christchurch, in a commemoration rivalled by only that of Michael Joseph Savage.

There are many parallels between the two men: both died in office, both were humanitarians and both were loved by Kiwis and respected by their opponents.

Kirk grew up in poverty – he caught ducks on the banks of the Avon river in Christchurch to help feed his family – but didn’t let that hold him back. After leaving school at the age of 12, he worked in a series of manual trades before making the move to politics on a local body level. His political career moved fast: he became mayor of Kaiapoi at the age of 30. Four years later he was the MP for Lyttelton, before becoming Labour party leader, MP for Sydenham and ultimately, Prime Minister.

Kirk grew up in poverty – he caught ducks on the banks of the Avon river in Christchurch to help feed his family – but didn’t let that hold him back. After leaving school at the age of 12, he worked in a series of manual trades before making the move to politics on a local body level. His political career moved fast: he became mayor of Kaiapoi at the age of 30. Four years later he was the MP for Lyttelton, before becoming Labour party leader, MP for Sydenham and ultimately, Prime Minister.

He worked to move the party on from its cloth-cap heritage in an effort to capture a broader electoral base, saying he wanted Labour to become “the natural party of New Zealand”. It’s safe to say, he was successful in his quest.

He once famously said that people don’t want much, just “Someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work and something to hope for”. That sentiment still rings true today and this book looks at the leadership of the man who was our last true working-class PM, his successes (including on the world stage) and also the difficulties he faced when the oil shocks of the early 1970s trampled all over New Zealand’s economy.

While a social conservative who expanded the welfare state and with strong connections and understanding of “ordinary” New Zealanders, Kirk wasn’t scared to rock the boat. A lot of Kiwis think of David Lange when it comes to our “no nukes” policies, but Kirk’s protesting against the French testing nuclear weapons in the Pacific Ocean was the trigger for our government and Australia to take France to the International Court of Justice in 1972, and he sent two Navy frigates into the test zone area at Mururoa Atoll the following year.

He also stopped the planned Springboks rugby tour of 1973 because of the apartheid regime in South Africa (although a later tour took place in 1981 under Rob Muldoon) and he spoke out against United States foreign policy. That might not seem like such a big deal to younger readers, but 40-odd years ago, New Zealand was a much younger nation that was, in many ways, still finding its way in the world. And there were few countries that spoke out about the policies of other, much larger and much more powerful countries. He brought our troops home from Vietnam, ending an eight-year involvement, he put an end to compulsory military training, and he started the process of recognising Treaty issues.

Kirk even inspired the now legendary song Big Norm that topped the charts and won a gold disc for Wellington duo Ebony in 1974. The last telegram “Big Norm” sent before his death was Don Wilson and Stefan Brown, aka Ebony, congratulating them on their success. They received their award the day before Kirk died.

He was inclusive, strong and respected, and inspirational. His legacy is that even now, four-plus decades down the track, we still remember his with fondness and respect. David Grant has done a fine job of telling his story in a way that highlights his greatness along with his humility, while still showing him as a decent Kiwi bloke who could relate to anyone.

Kirk once said: “Democracy doesn’t belong to the government or to prime ministers, it belongs to the people.” And that really sums up a man who truly was a mighty totara in New Zealand politics and New Zealand society.